|

Site Map |

|

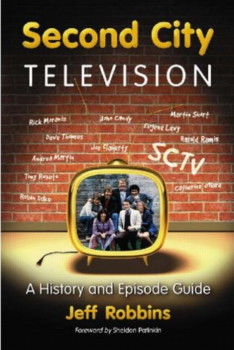

FEATURES - A HISTORY AND EPISODE GUIDE by Jeff Robbins |

|

A History and Episode Guide Long-time SCTV Guide contributor and fan Jeff Robbins has written a definitive guide to the show - available now from amazon.com, amazon.ca, or direct from the publisher McFarland. What follows are two excerpts from Robbins' book, the Preface and show review for episode 84 (Moral Majority). Preface Television has always been a copycat business. Even in the 1970s - before there was FOX, the WB, UPN, the CW, My Network TV, and hundreds of cable channels to choose from. Before there was iTunes, podcasts, Innertube, NBC Rewind, YouTube, on demand, pay-per-view... in short, even when there was less demand for content and less content to copy, television was a copycat business. The logic has always been that if something worked once, it can work again. So it was that when a meeting was called among a talented group of performers and writers in the spring of 1976, the impetus behind the gathering wasn't to create what Canada's newsmagazine Macleans would later call "one of the most successful pieces of television art ever made"; rather, the goals were to get rich and to get famous - something that was quickly happening to the stars, writers, and producers of a new late-night NBC television program called Saturday Night. The assemblage was held in Toronto on Lombard Street at the Old Firehall, a reconverted fire station, which, not coincidentally, happened to be the Canadian home of the Second City, the famed improvisational comedy theatre company that was originally founded in Chicago in 1959 and had expanded to Toronto in 1973. Second City revues, then as now, featured a first half of scripted comedy scenes, followed by a second half of improvisations based on ideas submitted by the audience. Early alumni of the Second City included Alan Arkin, Joan Rivers, Robert Klein, Fred Willard, and Peter Boyle. The group gathered on that day - especially Second City stage performers Joe Flaherty, Eugene Levy, Harold Ramis, and Dave Thomas - had more reason than most to want to duplicate the success of Saturday Night's Not Ready for Prime Time Players. Three of the emerging stars of NBC's new sketch show, Dan Aykroyd, John Belushi, and Gilda Radner, had honed their comedic skills at the Second City. Driven by envy, pride, and the knowledge that Saturday Night producer Lorne Michaels hadn't drafted anywhere near all of Second City's best talent, the decision to mount another television show was made. The concept of Second City Television - a satire of television programming presented in the format of a broadcast day from a low-budget TV station - arose fairly quickly during the meeting, and has most often been specifically credited to Second City stage director Del Close and eventual SCTV associate producer Sheldon Patinkin. The concept was a brilliant one and stuck for 135 shows - 52 half-hours for Canada's Global TV, 26 half-hours for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, 39 90-minute shows for NBC, and 18 45-minute shows for Cinemax. But the cast, who doubled as writers, and who at various times included (in addition to Flaherty, Levy, Ramis, and Thomas) Second City stage veterans John Candy, Catherine O'Hara, Andrea Martin, Martin Short, Robin Duke, Tony Rosato, and former disc jockey Rick Moranis, was too ambitious to forever stay within the confines of that concept. Only the first few SCTV episodes actually presented a "broadcast day" from the sign-on program "Sunrise Semester" to the sign-off sermonette "Words to Live By." Sketches soon became longer and more complex. The cast introduced countless characters and then evolved them far more dramatically than the characters their former Second City colleagues were performing on Saturday Night Live: Levy's Bobby Bittman went from hack comedian to hack dramatic actor in a remake of On the Waterfront. Candy's Johnny LaRue went from sleazy showbiz mogul to sleazy political candidate. Flaherty's unctuous host Sammy Maudlin went from presiding over a parody of Sammy Davis, Jr.'s talk show Sammy & Company to presiding over a parody of Alan Thicke's talk show Thicke of the Night. SCTV's actors and writers decided early on that it wasn't always enough to parody one television show or film at a time or even one genre of TV show or film at a time: Their style of "multi-layered" parodies became perhaps the show's signature ingredient. The show-length "Fantasy Island" sketch in SCTV's second season (show 44), which combined elements of the frothy ABC primetime hit, the Bob Hope-Bing Crosby series of "road" movies, and the film classics Casablanca and The Wizard of Oz, is the most successful example of this groundbreaking comedic style. Another early innovation was to introduce viewers of SCTV not just to the station's programming, but also to the station's backstage machinations. These behind-the-scenes segments evolved exponentially when NBC picked up the program in 1981, scheduled it after The Tonight Show on Friday nights, and expanded its length from 30 to 90 minutes. Some of SCTV's most celebrated installments feature these ambitious storylines (usually referred to as "wraparounds" for how they "wrapped around" stand-alone sketches) that were produced during the NBC years, such as the Emmy Award-winning Moral Majority (show 84) and Sweeps Week (show 115) episodes, the Russian Show (show 88), and the extended Godfather parody (show 93). It was during the NBC years, 1981-1983, that SCTV reached arguably its creative and critical apex. Although the show had had a convoluted production and distribution history - moving from Global TV to the CBC to NBC - and often seemed to be on the brink of extinction, it landed on American network TV at the right time: What passed for comedy on the three major networks at the beginning of the eighties was largely terrible, and, most significantly for SCTV, its main competitors, Saturday Night Live and especially Fridays, were reviled for presenting mostly juvenile drug-based humor. Television critics universally hailed SCTV as one of the best things on the air. Unfortunately, SCTV's critical success never fully transformed into massive commercial success, and after two years on NBC, it became clear that SCTV was not going to rival Saturday Night Live for longevity. SCTV was expensive to produce (especially considering the very late hour at which it aired), its ratings were stagnant, Rick Moranis and Dave Thomas had left to produce the Bob and Doug McKenzie film Strange Brew, Catherine O'Hara had also defected, and it was inevitable that SCTV's biggest star, John Candy, would also depart to focus on feature films. After negotiations with NBC - which are humorously recalled by Flaherty and Levy on one of SCTV's DVD releases - fell apart, SCTV became the first original programming on the fledgling cable network Cinemax, which aired the show's final season of 18 episodes from November of 1983 to July of 1984. Despite declarations from the cast and producers that being on cable television would rejuvenate SCTV by freeing it from broadcast network restrictions, the final season - dubbed SCTV Channel - was sub-par. The four-person cast was too small (some of the cast rejected plans to expand the group by bringing in interested outsiders such as Jim Carrey, Jim Belushi, and Billy Crystal), and the writers were burned out. It didn't help that since Cinemax had only two million subscribers, leaving most SCTV fans simply unable to watch. SCTV faded away, this time for good, after Cinemax aired its final episode - SCTV's 135th - on July 17, 1984. But SCTV continued to thrive after production ceased: A year after its run on Cinemax ended, newly repackaged syndicated reruns appeared. Since many markets aired these reruns in more accessible time periods than SCTV had previously been afforded, the show was given another chance to expand its audience. Perhaps more significantly, the show's legacy and influence continued to grow enormously in the comedy world; one could argue that although without Saturday Night Live there would have been no Fridays, without SCTV, there might have been no Ben Stiller Show, Kids in the Hall, The State, Upright Citizens Brigade, or Mr. Show. (Entertainment Weekly dubbed The Ben Stiller Show "SCTV with Better Hair.") Conan O'Brien has been one of the more vocal and visible devotees of SCTV, even hosting a cast reunion at the 1999 Aspen U.S. Comedy Arts Festival, which appears on Volume One of the SCTV DVDs. A listen to DVD commentaries of influential programs such as Freaks & Geeks, Undeclared, and even The Simpsons reveals creators' debts to SCTV. More significant in relation to the book you are holding is the impact SCTV had on me, which began when I was just nine years old. But my earliest remembrances of the show are not of laughter, but of sheer terror. It was show 12's "Movie of the Week" sketch - not a Count Floyd piece; every SCTV fan knows there's nothing scary about Count Floyd or the movies he presents - that I found horrifying. The sketch featured John Candy as a taxidermist who takes his girlfriend home to meet his parents. But his parents, like the numerous animals adorning their walls, are also dead and stuffed. The piece ends with Candy's petrified girlfriend frantically phoning for a police officer, who arrives quickly but is of little help as he too is dead and stuffed. Somehow this initially disturbing exposure to SCTV did not deter me from tuning in again; upon further viewing I realized that the program was a comedy show unlike any I had ever seen. Quickly SCTV began to play a huge role in my adolescence, particularly when the program moved from first-run syndication to NBC on May 15, 1981. The night of the network premiere was especially exciting, and I distinctly recall watching the first NBC installment in my bedroom - on my tiny black-and-white set - while my parents and older sister slept. Although I could have watched SCTV on a bigger (and color) TV, there was something appealing about watching my show on my TV. And since no one else in my fourth-grade class knew of the program, I felt strongly that SCTV was my show. Which brings me to my book: Despite the show's unparalleled comedic legacy, despite its loyal fan base of TV critics and viewers, despite producing such stars as John Candy, Eugene Levy, Catherine O'Hara, and Martin Short, despite its special star on Canada's Walk of Fame, despite being named a "Masterwork" by the Audio-Visual Preservation Trust of Canada, and despite its recent resurgence on "TV on DVD" shelves, precious little of substance has been written about SCTV. Dave Thomas has collected a very enjoyable book of cast remembrances, while Sheldon Patinkin's book The Second City: Backstage at the World's Greatest Comedy Theater, included a single chapter devoted to SCTV. But nearly nothing has been written on what makes SCTV such a standout: the shows themselves. Which is a shame, since not only does SCTV deserve such treatment, but, given the density of its material and its often-obscure targets for parody, it almost demands it. The purpose of this book is therefore to provide followers and newcomers alike with an ultimate SCTV reference guide, which traces not only the appearances, evolution, and development of its many legendary characters, but also reveals the sources of SCTV's parodies, most of which aren't as obvious or well-known (especially decades after production) as show 15's Leave It to Beaver satire or show 113's lampoon of Cagney & Lacey ("Koffler & Meltzer"). In short, this book is a history of the Second City Television programming that originated from the fictional town of Melonville. (For a backstage history of SCTV that originated from the very real towns of Toronto and Edmonton, I recommend that you track down Dave Thomas's SCTV: Behind the Scenes.) To complete this task, I visited and revisited innumerable times my extensive SCTV tape library, which I have been compiling since 1981 (when my parents bought their first VCR) and which grew in the late nineties through Internet tape-trading. For adding to the archives, I need to thank Dwight Hodge, Michael Delaney, and others whose names have sadly been deleted along with erased e-mail correspondence. I compared and contrasted different versions of sketches and shows culled from Canadian syndication, American syndication, NBC, Cinemax, and various best-of incarnations. In the latter stages of compiling this book, Shout! Factory began to release SCTV DVDs, which in many cases (largely due to the difficulty of obtaining music clearances) presented even additional variations of material. I also rented or purchased and studied countless films - many not easy to find and many of which I admit I was initially unfamiliar with - in order to detail how they were then parodied by SCTV. (Special thanks here to my good friend Jeremy Fredriksen for tracking down a copy of the out-of-print film disaster - not disaster film - The Oscar.) Lastly, I revisited my library of reviews and other writings on SCTV that I've compiled since the early eighties. These reference sources and others are noted at the back of this volume. In summation, this book is not just for those who were paying attention when SCTV was originally in production. It is also for those who are just now catching up with SCTV on DVD. Although the show ended its run on July 17, 1984, SCTV will always be for me and for many others - as the show's opening credits proudly proclaim - "on the air!" For each episode detailed on the following pages, the list of sketches is a chronological account of major pieces on that show. Bumpers, opening credits, and commercial breaks are not listed. Also, if a sketch played as a whole but was interrupted by a real commercial break, the piece is listed as one sketch and not as a "two-parter." Conversely, if a sketch was interrupted for a commercial parody or other SCTV-produced piece, the interrupted sketch is noted as having two (or more) parts. Show 84 (SCTV Network 90)

This quintessential episode of SCTV was awarded the 1982 Emmy Award for Outstanding Writing in a Variety or Music Program. As in the last episode, this show's wraparound takes up about a third of the program. But here SCTV takes on an issue weightier than Johnny LaRue. To begin at the beginning: This episode of SCTV Network 90 was originally broadcast on NBC on July 10, 1981. In February of that year, the Reverend Donald E. Wildmon, in conjunction with the Reverend Jerry Falwell's Moral Majority group, created the Coalition for Better Television. Wildmon's tactics were simple - he, along with thousands of members of his coalition, planned to monitor television shows and then rank them based on sex, violence, and profanity. Then, after deciding which shows were most offensive, he would retaliate - not against the producers of the offending shows or against the networks that aired them, but against the advertisers who sponsored them. Wildmon's methods had already proven successful without the support of Falwell's Moral Majority: In the late seventies, after facing pressure from Wildmon and his followers, Sears cancelled its ads on the ABC programs Three's Company and Charlie's Angels. And not long before this SCTV episode aired, advertisers were again beginning to crack under the pressure of Wildmon's group - on June 16, 1981, the chairman of Procter and Gamble - the leading television advertiser at the time with annual expenditures estimated at $500 million - gave a speech announcing that, because of program content, his company had withdrawn advertising from 50 television shows in just the past year. One of Procter and Gamble's largest product categories at the time was household cleansers, including laundry products. So it's no coincidence that this SCTV episode attacking the tactics of Wildmon and Falwell involves a new SCTV advertiser named Sunbright that manufactures cleaning supplies. The two SCTV characters that are asked to compromise themselves the most in order to placate Sunbright are the morally questionable duo of Guy Caballero and Dave Thomas's Bill Needle, the latter making his first Network 90 appearance. The reasons for wanting to keep Sunbright happy are simple: Guy claims the company has agreed to invest $25 million annually in advertising. It's no surprise that of the two, the money-hungry Guy is most willing to do whatever it takes to make Sunbright - or any advertiser - happy. In the first wraparound segment, his desk littered with Sunbright products, Flaherty sums up the issue at stake - that there are outside pressure groups trying to "make television more acceptable to you and me as fine Americans." Guy's opinion of such pressure groups? "Everyone has a right," Guy says, "to his or her opinion as long as they've allied themselves with any of our sponsors." This eagerness to put programming decisions into the hands of advertisers and the pressure groups they fear is made clearer when Guy is asked by two Sunbright executives (O'Hara and Moranis, parodying two NBC executives assigned to SCTV), "if certain pressure groups decided to stop buying Sunbright, would you drop certain programs?" Guy of course readily agrees, suggesting that producer Norman Lear - who had founded a group opposed to Falwell and Wildmon called the People for the American Way in 1980 - should worry about such things. "I'm in business," Guy states, succinctly summarizing his priorities as a broadcaster. Of course Lear was just one of the many critics of the Moral Majority, and Bill Needle represents their opinions on his new program, "Critic's Corner." In a vociferous diatribe, Thomas's Needle screams about the insanity of "a small group of people" who "dictate the private and personal choices of the nation by holding a gun to the corporations that do the sponsoring." Needle is entitled to his opinion, but Sunbright is also entitled to not pay for his forum, and a Sunbright commercial scheduled for Needle's show is pulled in progress. Thomas's Needle then immediately switches gears, stating that if a small group of Nielsen families can decide what America watches, why not the Moral Majority? Never mind that a randomly selected group of Nielsen families don't have an organized political or moral agenda, but the about-face saves his job thanks to a stamp of approval given by Sunbright executives. The approval even extends to a Sunbright spokesperson job for Needle, but his convictions get the better of him and he storms off the set of a live commercial, leaving Sunbright to ultimately pull their lucrative advertising off SCTV for good. Of course once the money is off the table, Guy indignantly lashes out at the Moral Majority: "We here at SCTV feel strongly that television should not be subject to the whims of any pressure group; nor should they be subject to the whims of any sponsor!" Unfortunately for Caballero, insult is added to injury as a major "alternative" sponsor - Harry's Sex Shop - also cancels its advertising since the programs on SCTV are not "violent or sexy enough." This turn of events leads Caballero to decide on a "pledge week," which plays a major role in the next episode of SCTV Network 90. What makes this wraparound most effective is how SCTV combines a story involving its fictional characters with a real life subject no doubt unfamiliar to many of its viewers. Because even new viewers already recognize Guy Caballero as someone who acts with profit as his only motive, his embrace of these pressure groups and the advertisers that bow to them is immediately suspicious. And because Bill Needle is at the same time both less familiar but more relatable, viewers can identify with Needle's disgust and agree with his choice to ultimately rebel against Sunbright and their money. As seen through Needle's eyes, viewers reject the idea of pressure groups and advertisers dictating programming choices. But the story ends on a cautionary note: Since the full impact that Wildmon and Falwell would have on television programming remained to be seen, SCTV had to guess at their success rate. The show ends up taking the view that the Moral Majority and the Coalition for Better Television would indeed have a major impact; if SCTV is to be an example of what would happen to the "real" networks, then the show prophesizes that pullout from advertisers would leave networks with unsold time and greatly diminished profits. Of course no "real" network would or could make the immediate decision to have a "pledge week," so the end result as SCTV sees it would be for the networks to ultimately have to cave in to advertiser boycotts, allowing the pressure groups to emerge victorious. The real-life version played itself out very differently; Wildmon and Falwell eventually had a falling-out, and Wildmon's most ambitious boycott - of RCA, the then-owner of NBC - proved unsuccessful. Wildmon's power then greatly eroded (his Coalition for Better Television crumbled in 1982, seven years before the Moral Majority disbanded), although he has returned many times since with successful advertiser boycotts of shows such as Married ... with Children and Saturday Night Live. Despite keeping his name in the newspapers, Wildmon's mission to "clean up" television has been largely unsuccessful. But even decades after this episode of SCTV originally aired, pressure groups (such as the Parents Television Council) continue to exist, forever hoping to, in the words of Guy Caballero, "Make television more acceptable to you and me as fine Americans." Aside from the wraparound, there is much impressive material in this episode. One sketch that the Reverend Wildmon wouldn't approve of (since it features women in states of partial undress) is "Dr. Tongue's 3-D House of Stewardesses." The "3-D" series of sketches is familiar to veteran SCTV viewers, but this is the preeminent "3-D" piece. Note that this is the first "Monster Chiller Horror Theatre" in which host Count Floyd doesn't mind that the movie isn't scary - after all, it features attractive women cavorting around in their underwear (including Catherine, who cannot control her laughter). "Did you get a good look at those chicks?" is Floyd's immediate response to the film, a line only improved by remembering that Floyd's target audience is children. Network 90 viewers discover in this episode that Count Floyd is actually played by "SCTV News" co-anchor Floyd Robertson, who we learn has been away taking care of a drinking problem - a problem that had been heretofore hinted at several times in the first three seasons of SCTV. In reality, it doesn't appear that Robertson has entirely sobered up, a fact that could be the fault of a lackadaisical policy at his rehab center; in an ad for the treatment facility, Floyd claims that "they may not help you stop drinking, but maybe you can cut down." Even with longtime characters like Floyd Robertson and Dr. Tongue to work with, cast members were busy churning out new personas that would play big roles in the show's future. Here Andrea Martin's Mrs. Falbo, the host of the children's show "Mrs. Falbo's Tiny Town," makes her debut. The idea behind the sketch, that a children's show would feature material wildly inappropriate for children, is not original, but the gentle execution is unique and certainly a far cry from kids' show parodies such as seen in the film The Groove Tube, in which a clown reads excerpts from Fanny Hill. Mrs. Falbo intends to be educational, but she's not very bright; for example, she kills a goldfish while attempting to explain how fish breathe. She's also the victim of bad timing - while looking at the king and queen through her "magic telescope," she inadvertently catches them (in a scene censored for off-net syndication) engaging in some bizarre sexual activity. Although an argument could be made that making fun of kids' shows is typical fare for a comedy show, there's nothing typical about "The Merv Griffith Show" sketch. Another example of the multi-layered style of parody that SCTV excelled in, this sketch is an ingenious parody of both The Merv Griffin Show and The Andy Griffith Show, with Moranis playing Merv as Andy. Joe Flaherty summed up the sketch's genesis: "We were bored doing straight-on parodies. Why do just Merv Griffin? Why not do Merv Griffin doing 'The Andy Griffith Show?'" Flaherty contributes a mean Barney Fife to the piece, but as good as he and Moranis are, it is Levy's wonderfully uncanny Floyd the Barber impression that steals the piece. This sketch would become one of SCTV's most celebrated pieces. Besides "Merv Griffith," Rick's other showcase piece on this episode is the second (and last) "Gerry Todd Show." This sketch repeats some elements from the first installment (show 80), but Rick includes one original thread - a memorable impression of notoriously deep-throated singer Michael McDonald - that makes this "Gerry Todd Show" an improvement on the first. Moranis as McDonald is everywhere in this sketch - doing back-up vocals for a Tom Monroe (see show 79) version of "Downtown," providing the vocals for a low-rent carpet commercial, and, in the most inspired twist, starring in a video for Christopher Cross's then-hit "Ride Like the Wind." The video shows McDonald frantically driving to the studio to record his backup vocals for the Cross track; when the track is complete, McDonald's only spoken words - a ridiculously cavernous line reading of "OK. See ya" - provide a great punchline. From Second City Television: A History and Episode Guide © 2008 Jeff Robbins by permission of McFarland & Company, Inc., Box 611, Jefferson NC 28640. www.mcfarlandpub.com. |

© 2008 SCTVGuide. All Rights Reserved.