|

Site Map |

|

FEATURES - A DAY IN THE LIFE "At the time I was just trying to keep the doors open." |

|

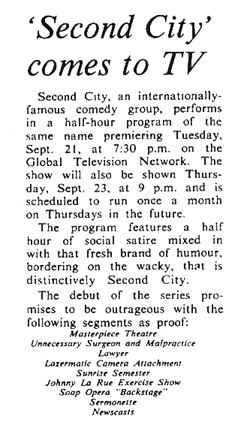

The following article about the genesis of SCTV on Global is from the Ottawa Citizen. A day in the life of a young station Second City Television was the first, fated, Canadian cult hit for a brash young broadcaster with big ideals Tony Atherton, Ottawa Citizen (Wednesday, November 27, 2002)

That's it -- the most unprepossessing birth of a major television series ever recorded. The show they agreed to co-produce that spring day in 1976 would collect 13 Emmy nominations (winning twice), and be in nightly reruns on a major U.S network nearly a generation after its cancellation. Entertainment Weekly would include it on its list of the 100 greatest shows of all time. For six seasons over eight years, it would nurture most of the biggest Canadian celebrities of its generation: Hollywood movie stars, international TV luminaries, Broadway divas, entertainment moguls. But it would nearly go bust when it was still no more than a cult fad, thanks to in-fighting among the owners of its financially troubled young broadcaster. The show, then called Second City Television, would rise again to fulfil its destiny as SCTV, SCTV Network 90 and SCTV Network, but the broadcaster, Global Television, would have lost a show whose success might have approximated the lofty ambitions of the station's founders. The use of the word Global in the corporate name of the Toronto TV station that would become the linchpin of Canada's third national broadcaster is not mere bravado. It is a precise representation of the remarkable intent of the station's founder. Ten years before a brash upstart named Ted Turner created the world's first "superstation" in Atlanta, Al Bruner had begun his crusade to bring Canadian television to the world via satellite. Bruner was sales manager at Hamilton independent station CHCH when he began to think globally. He wanted to launch an all-Canadian TV satellite that could beam a Canadian signal to transmitters around the globe. His idea was that one station could serve the entire country and earn enough on national advertising to be able to afford to make the kind of Canadian programming that private stations serving local markets had been unwilling to invest in. In the early '70s, he brought his scheme to the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission. CRTC chairman Pierre Juneau had made clear he felt private broadcasters hadn't been pulling their weight in the creation of Canadian content. He appreciated Bruner's chutzpah, but decided the proposal was more than the broadcaster could handle. The CRTC rejected the bid. Bruner then reshaped Global as a microwave-fed system of retransmitters serving southern Ontario from a single station in Toronto. He promised the station would spend a whopping $8 million a year on original Canadian programming. The CRTC was charmed, and gave a thumbs up. The CRTC was open to all kinds of TV innovation, looking for any way to increase Canadian program production. In 1974, it was delighted by the symbolism of a venture by a Manitoba politician with an entrepreneurial bent. Israel Asper, then the leader of the Manitoba Liberal party, bought a North Dakota TV station, KCND, moved its equipment north of the border and created CKND in Winnipeg. In a bit of happenstance that was to prove significant, one of Asper's minor partners in the company --eventually known as CanWest Capital, which now owns the Citizen -- was Global consultant Seymour Epstein. As Asper was making his move in Winnipeg, Bruner was launching Global in Toronto, and it was clear the latter scheme was underfinanced. "Bruner had big-time plans for programming, a little too ambitious for a fledgling network" says Gerry Appleton, a producer Bruner brought from CHCH. "But they were honourable plans. He was really going to make a mark on the Canadian production community." Instead of seeking relief on programming commitments, Bruner bulled ahead, intent on spending the millions he had promised in the first year. Almost a quarter of the $8 million went to a daily, 90-minute variety show, Everything Goes, hosted by Catherine McKinnon. Meanwhile, actor/comedian Don Harron was using up more of Bruner's capital in an Ottawa-made satirical sketch-comedy series that featured Barbara Hamilton, Jack Duffy and Ottawa cut-ups Les Lye and Bill Luxton. Shhh! It's the News, was a weekly send-up of recent headlines. Cartoonist Ben Wicks was given a talk show, and veteran broadcaster Pierre Berton had two shows -- The Great Debate, a lively panel show, and My Country, which related the stories of famous Canadians. Patrick Watson produced the only creature of this programming blitz to maintain a profile in reruns. Witness to Yesterday featured Watson interviewing Canadian actors in period costume playing figures from history. Unfortunately for these shows, Global was losing $50,000 a day, and by its third month was teetering on the brink of bankruptcy. Epstein called upon his Winnipeg partners, Asper and Paul Morton. They brought in Allan Slaight, who had made his mark programming CHUM radio stations. For about $7 million, the syndicate took over what potentially was the richest single licence ever issued by the CRTC -- one station with a region-wide reach. But changes had to be made if Global was to survive. The original Canadian programming was scuttled, staff were let go and the new owners concentrated on finding lucrative U.S. programming. By 1976, things had turned around enough that its new president, Allan Slaight, started thinking about making his own mark in Canadian programming. It may have been his undoing. - - - About the time Bruner was sinking in debt, Bernie Sahlins and Joyce Pivens were spinning similarly out of control with their own venture. Sahlins and Piven, envoys from a successful Chicago nightclub called Second City, had come to Toronto a year earlier intent on expanding their empire. They were foiled by the city's blue-nosed liquor laws: They couldn't get a licence, and couldn't make a go of it without one. The first incarnation of Toronto's Second City, in a theatre on Adelaide Street, went bust despite a cast that included an imaginative couple from Ottawa -- Dan Aykroyd and Valri Bromfield -- brassy Toronto actress Jayne Eastwood, her quieter castmate from the Toronto production of Godspell, Gilda Radner, and a couple of Chicago Second City imports -- Joe Flaherty and Brian Doyle-Murray. Another larger-than-life Toronto actor had auditioned, but 19-year-old John Candy was so magnetic that Sahlins sent him to the main stage in Chicago. Unwilling to give up on Toronto completely, Sahlins sold the Second City franchise -- for $1 -- to Andrew Alexander, a knockabout Toronto theatre producer who owned a piece of a local restaurant and had a track record with the forbidding Liquor Licensing Board. In 1974, Alexander reopened Second City in a converted firehall on Lombard Street. The new cast included a chipmunk-cheeked former advertising copy writer named Dave Thomas, and a sloe-eyed flirt who had waited tables at the Adelaide Street club, Catherine O'Hara. A year later, Toronto's Second City was still in business, solvent and increasingly popular. It was also under new pressure: A Toronto comedian named Lorne Michaels had convinced NBC to underwrite a weekly sketch show in the vein of Second City and the satirical magazine National Lampoon. Michaels' Saturday Night Live had plundered members from Second City casts, including Aykroyd and Radner from Toronto. Sahlins figured the best defence was a good offence, and approached Alexander about producing a Second City TV show. Alexander was wary. "At the time I was just trying to keep the doors open." But, he adds, "I was concerned: I had a terrific cast and I wanted to keep them together." In another part of the city, Gerry Appleton, Global's executive producer, was being told by boss Allan Slaight "to find a vehicle that we might do that was truly, truly Canadian," Appleton recalls. So when Alexander called, Global was in a receptive mood. Alexander and Sahlins had brainstormed at the Firehall with some of Second City's best writers, including Thomas, Flaherty, halo-haired Eugene Levy (another Godspell alumnus), and Harold Ramis, a lanky, sometime joke writer for Playboy who had been part of Chicago troupe. Del Close, a Second City stage director, suggested during the meeting that the TV show's concept should be the programming day of a small TV station. Alexander brought this concept to his meeting with Slaight and Appleton, which was to the point: Global would provide the hard production costs -- studios, crews, cameras, sets, lighting and make-up -- for seven half-hour shows, while Alexander would take care of the creative costs -- the cast members, who were writers as well as performers. The deal would later be extended to 26 shows, and 29 more in the second season. The problem was that almost nobody connected to the show knew exactly what they were doing. The cast -- Flaherty, Thomas, Levy, Ramis, O'Hara and Andrea Martin, who had been part of the Toronto stage show, plus a newly repatriated John Candy -- had never made TV, and few at Global had ever made this kind of TV. The Global director on the first shows, Milad Bessada, had a wealth of TV experience, but much of it was in his homeland, Egypt. In his memoir of the show, SCTV: Behind the Scenes, Thomas suggests Bessada missed many of the show's pop-culture references. Before long the show settled into the assembly-line process it required to meet its slim budget. Whole scenes were blocked and shot in as little as half an hour. Stage hands recycled endless sets, most of them painfully chintzy. "They just didn't have the money for the more expensive sets that came later," says Global supervising producer Dennis Bilbrough, who was a production assistant in 1976. "Many a night, we'd strip the sets down and repaint them another colour for the next day's scene. We hung props, brought in plants from home and did the best we could to change the look of the set." Alexander and Sahlins were convinced they would make a killing with the show in the U.S. They brought an unfinished version of the first episode to New York and met Bob Shanks, an NBC executive working for programming whiz Fred Silverman. "We felt pretty cocky," says Alexander. "We thought we had something special." So did Shanks, says Alexander. "He said, 'I love this, I love this. This is going to be a show we run right after Johnny Carson.' We walked out of there thinking, 'This is pretty simple: our first half-hour and already we're on a network.' About two weeks later we got a call from Bob Shanks saying Silverman had seen the show and thought it was too intellectual." No sale. Instead, they made a deal with syndicator Jack Rhodes, who sold the series piecemeal across the U.S., providing just enough cash for production to carry on. By its second season, Second City Television was a cult hit. "By Canadian standards it was definitely beginning to make some inroads," says Alexander. However, he notes, "it was still one of those shows that had to be delivered at the right price in the American market to justify even getting on the air." Appleton had no doubt it was a matter of time before the series was as big with viewers as it was with Global's production staff. And yet halfway through the first season, the means of the series' demise was already in the works. Asper and Morton had concerns about where Slaight was taking the company, according to From Winnipeg to the World: The CanWest Global Story, a history published by CanWest. "Allan wanted us to be quiet," Israel Asper says in the book. "He wanted us to stay in Winnipeg and not ask so many questions . . . We were very active and he resented it." Slaight triggered a shotgun clause that had been written into the takeover deal. He made an offer to buy the Winnipeg partners out, and they had 30 days to agree or counter-offer. Slaight was caught flat-footed when Asper and Morton raised the capital to respond. He was out, and David Mintz was in. Mintz, a veteran U.S. broadcaster, wouldn't become president until 1979, but by Second City's second season he was a massively successful independent sales rep for Global who was convinced that U.S. programming was the station's greatest potential asset. He wrangled the Canadian rights to many popular American shows -- "especially The Love Boat," says the company history, in reference to Mintz's use of Love Boat reruns to increase revenues. "I was assured of money coming in," Mintz says in the book. "So we let them call us that for a year, 'The Love Boat Network.' It was the difference in making us profitable." As part of the fiscal retrenching, Global cancelled Second City, saying it was shifting its Canadian programming emphasis from studio programming to news. ("CanWest was not involved in management except at the board level," Israel Asper said this week. "We assumed management only in 1990.") Alexander and Sahlins pitched the series to CBC. It was a Canadian show that attracted the young audience the public network desperately needed -- a natural fit, Alexander figured. But the CBC wasn't in the market for comedy. "We were definitely in a place where it didn't look like the show was going to have a future," says Alexander. Second City Television went dark for a year before a deal was struck with ITV, the Alberta independent station. The show was syndicated in Canada and the U. S. until CBC bought the Canadian rights. By its fourth season, NBC picked up the show and expand it to 90 minutes, though it would continue to be taped at ITV. Appleton says he was hurt by the decision to axe the show. "I think, in hindsight, we betrayed ourselves. I don't think Dave was (making) anything but a quick business decision." Global recovered and grew into Canada's third national network. Appleton stayed for another 10 years before leaving to start his own production house. He still looks back fondly on the time when a starry-eyed entrepreneur named Al Bruner entertained grand notions about Canadian programming. Canadian Television at 50: Third of a Five-Part Series. |

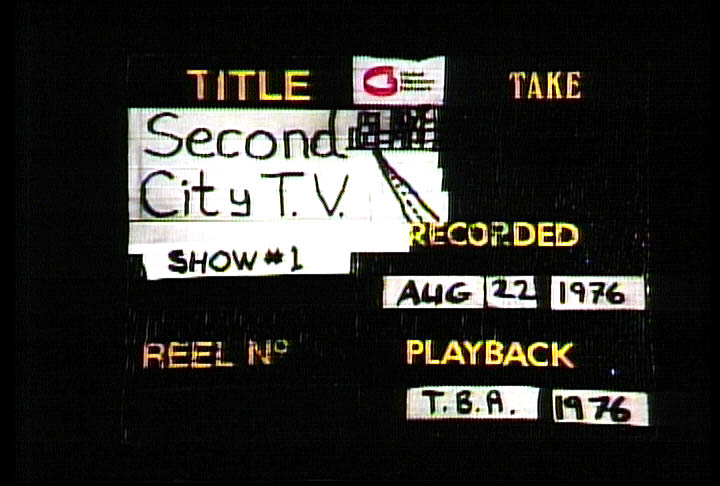

Slate from the taping of the very first episode

© 2010 SCTVGuide. All Rights Reserved.

In the utilitarian boardroom of a squat former factory in a Toronto industrial park, a top-40 radio programmer charged with saving a near-bankrupt TV station meets with a former WHA hockey producer and a wet-behind-the-ears nightclub owner who can barely afford to keep his doors open. They talk for 20 minutes, scribbling notes on a sheet of paper, then shake hands.

In the utilitarian boardroom of a squat former factory in a Toronto industrial park, a top-40 radio programmer charged with saving a near-bankrupt TV station meets with a former WHA hockey producer and a wet-behind-the-ears nightclub owner who can barely afford to keep his doors open. They talk for 20 minutes, scribbling notes on a sheet of paper, then shake hands.